Image copyright

Getty Images

This summer marks 50 years since 400,000 people flocked to a field in upstate New York for “an Aquarian explosion” of “peace and music”.

The Woodstock music festival, held at a farm in Bethel, has come to symbolise much of the idealism of the 1960s. It is seen by many as the nexus of freedom, sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll which fuelled the countercultural movement of the decade.

To mark the anniversary of the legendary gathering we spoke to some of those who experienced the festival first-hand.

Jim Shelley was back at home in “pre-Springsteen” New Jersey for the summer after his first year at university in the conservative Midwest.

The “suburban white Catholic kid” was questioning the legitimacy of the Vietnam War and started to think “the direction the country was heading in politically was wrong”.

He had developed an interest in world music and French New Wave cinema, and felt increasingly at odds with mainstream society.

“I felt like an outsider. If you were like me, people didn’t like you. People didn’t agree with my views on the war,” he says. “People thought you were a nerd, or stupid, or strange.”

For the 19-year-old, Woodstock was the first time he felt others shared his world view.

Image copyright

Image copyright

Jim Shelley

Jim borrowed a 35mm camera and one roll of film to record the weekend. He isn’t in any of the photos he took: “Selfies weren’t invented yet”

“I had never experienced anything like that before,” he recalls. “I remember looking around at the crowds of people like me and thinking, ‘Look how many of us there are’.”

Jim describes Woodstock as “life-affirming, rather than life-changing”.

“The attitudes I had before I went to Woodstock, which were so out of place back home, were confirmed when I was there. Woodstock made me realise I was right and my ideas were legitimate.”

Image copyright

Image copyright

Jim Shelley

When asked who attended the festival Jim half-jokingly replies: “White kids getting sunburned”

His experience emboldened him and his then girlfriend – now wife – not to conform.

“My wife and I cared about the environment so we used recyclable nappies when our children were born. She was the only woman on the maternity ward to breastfeed. I was the only man to be in the delivery room. We wanted to do things differently, and we did.

“Woodstock didn’t teach me those ideals but it made me confident they were legitimate.”

Image copyright

Image copyright

Jim Shelley

Jim took this photograph from his sleeping bag on the Saturday of the festival

‘Smoking grass and rotting hay’

Casting his mind back to that August weekend in 1969, Jim recalls the two smells that came to mind – marijuana and rotting hay.

“I didn’t do drugs at that point. I was straight and guess I hadn’t had the opportunity. But there were lots of people smoking grass.

“But I wasn’t the only person not to smoke. People think it was everyone but it wasn’t.”

The heavy rain that lashed the site on the Friday had soaked into the mat of cut hay that covered the field. It soon began to rot.

“That rotting smell hung in the air. I remember it was not pleasant.”

Image copyright

Image copyright

Jim Shelley

Jim snapped this image of the crowd cheering after Santana performed

He says he appreciates the legacy of the festival much more now he is older.

“I was 19, I didn’t think it would have a lasting impact on my life. But I now understand it has become a symbol of liberation. It’s a broader symbolic event and a beacon of freedom.”

Patrick Colucci describes himself as “a broken young man” battling a “storm of self-doubt” in that summer of 1969. He was studying to be a priest, but was questioning his path.

It was a chance encounter on a park bench that led him to ride his Honda motorbike to Woodstock.

“A young girl shouted to me that she was leaving in a caravan the following afternoon, and that I could follow on my bike if I wanted. The next day I found myself in the back of a car caravan on the way to Bethel, New York.”

The influx of thousands of people to rural New York state overwhelmed the small roads. Patrick was stuck in traffic jams for hours.

“That’s when the girl got out of the car in front and walked over. She had long, flowing hair, was wearing jeans and was barefoot. She noted I had a bike and suggested we ride together along the side of the road to the farm 10 miles (16km) ahead.”

Patrick and the girl, Maria, spent the weekend together.

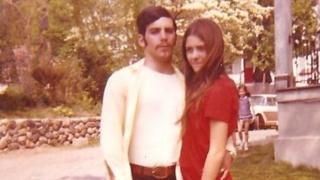

Image copyright

Image copyright

Patrick Colucci

Patrick and Maria after Woodstock

“I immediately felt the shackles of a lifetime of repression lift from my shoulders. There was a tremendous feeling of euphoria and the adrenaline of unbridled freedom in the air.

“That in my mind was when the Woodstock generation took flight and for the first time I felt I belonged,” he says.

Patrick and Maria married shortly after the festival and are now grandparents.

He hopes that the spirit of Woodstock can be “rekindled” and calls on his generation to “join forces with the young” to tackle issues such as climate change.

“If you are anything like me, the mud of Woodstock still squishes between your toes.”

Glenn Weiser was a 17-year-old high-school student studying classical guitar in 1969 – but he loved rock ‘n’ roll.

Glenn and a group of his “starry-eyed hippie” friends travelled to the festival from New Jersey.

He admits that while he remembers the music clearly, other details from the weekend are a bit hazy because they were all experimenting with LSD.

“That psychedelically inspired love that so many of the hippies really did seem to have at Woodstock and elsewhere is probably the thing I miss the most about the late 1960s.”

“Woodstock really was as fabulous as it was cracked up to be. It was wild and glorious. I left that weekend glowing. I was walking on air.”

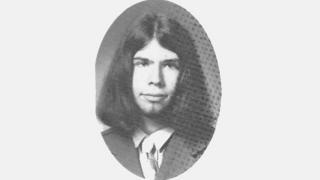

Image copyright

Image copyright

Glenn Weiser

Glenn Weiser a few months after the festival – he points out his tie in this photo is “Day-Glo”

While he was struck by the size of the “mighty crowd”, Glenn was unaware of the impact the festival would have.

“I got home and my parents told me that it was the main news story,” he says. “I had no idea.”

Glenn’s long hair and questioning of the Vietnam War was “most unpalatable” to his parents. But, seeing the number of young people who shared his ideas was reassuring for him.

“The ethos of peace and love was very real. I was a real believer in that gospel.”

‘A teeming squalid mess’

While the festival-goers we spoke to remembered Woodstock positively, not everyone looks back so fondly on the weekend.

American journalist Hendrik Hertzberg wrote in 1989 that the only true ecstasy to be found at Woodstock was “getting the hell out of there”.

He recalls traversing “a thick, slippery, brown river of boots and muck”, spending hours queuing for the toilet and dodging “chemically disoriented” passers-by.

This sentiment is echoed by Mark Hosenball who wrote an article in 2009 titled “I was at Woodstock. And I hated it”.

Rather than an attendee at the centre of a hazy hippie haven, he sees himself as victim of a “massive, teeming, squalid mess [of]… colossal traffic jams, torrential rain, reeking portable johns, barely edible food, and sprawling, disorganised crowds”.

All images copyright as shown.