Image copyright

Getty Images

The mirrored ceiling of the Shah Cheragh mausoleum, was Monir Farmanfarmaian’s biggest inspiration

Monir Farmanfarmaian looked up at the mosaic of mirrors that covered the mausoleum’s walls and ceiling. It was the moment that reshaped her artistic career.

“The very space seemed on fire, the lamps blazing in hundreds of thousands of reflections,” she would later write in her memoir. “I imagined myself standing inside a many-faceted diamond and looking out at the sun.

“It was a universe unto itself, architecture transformed into performance, all movement and fluid light, all solids fractured and dissolved in brilliance in space, in prayer. I was overwhelmed.”

The year was 1975, and the setting was the Shah Cheragh (King of Light) shrine in the Iranian city of Shiraz, that had been decorated in splintered mirrors since the 14th Century.

At the time she visited the shrine, Monir was already a recognised artist in the US and her native Iran, but the epiphany in Shiraz left her “fired up with ideas”, she wrote in her memoir, A Mirror Garden.

Monir left Iran and returned many times as the country underwent radical change over her life. But the influence of Iran, and of that moment, never left her work.

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian died on 20 April in Tehran, aged 97.

Monir Shahroudy, as she was born, was raised in the northern Iranian city of Qazvin among peach, almond and walnut trees. One of her earliest memories was of being chased through the bazaar by a camel she had unwisely decided to chide.

When she was seven, the family moved to Tehran, where her father had been elected to parliament, and young Monir got her first glimpse of the capital modernising under the Shah, Reza Shah Pahlavi.

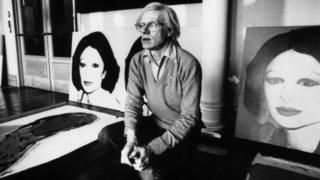

Image copyright

Image copyright

The Third Line

Monir Farmanfarmaian in her studio in 1975

Her first taste of art came in a once-a-week class in school, in which she was made to draw flowers or – on one confusing occasion – a jug sitting on a chair placed on a table.

“The teacher called this ‘still life’,” she wrote in A Mirror Garden. “It perplexed me at first, but still it was more fun than math.”

At the Fine Arts College of Tehran University, she met the man who would become her first husband, Manoucher. During World War Two, the couple moved to New York but it was a loveless marriage, with Monir making progress in her artistic studies and Manoucher holding a single-minded determination to become a famed artist.

“My role,” she wrote, “was to help that destiny along by providing financial support, unending praise, and gracious entertainment for any gallery owners and wielders of influence who crossed our path.”

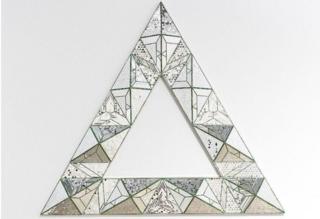

Image copyright

Image copyright

The Third Line

Pieces by Monir Farmanfarmaian displayed in Dubai in 2015

It was Monir herself who began to associate with artists of influence, spending time at the Tenth Street Club in Greenwich Village with Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Willem de Kooning, among others.

Another soon-to-be-famous name crossed Monir’s path when she started her first main job as a fashion illustrator with department store Bonwit Teller. His name was Andy Warhol, who was then working as a shoe illustrator.

“Conversation was not his strong suit,” she said, “but we made a connection in spite of his ghostly shyness.”

That connection was made again years later when Warhol travelled to Iran to paint the Shah and his wife. During his trip, he gave Monir the gift of a Marilyn Monroe print.

Image copyright

Image copyright

Getty Images

Warhol next to his “Princess of Iran” in 1977

Love – or at least the prospect of it – took Monir back to Iran in 1957, in the guise of Abol Farmanfarmaian, a man of aristocratic background who had babysat for her first daughter in New York.

With Monir’s divorce to her first husband finalised, she was wary, but welcomed the return to an evolving Iran 12 years after leaving. Just as the colours of Iran had never left her paintings of flowers, as her teachers noted, all her happy memories of her homeland had remained in place.

“I sat in a jet-lagged stupor and drank in the smells of home,” she wrote, “the sooty perfume of kerosene heaters with overtones of dill, parsley, fenugreek and aromatic rice that hinted at lunch, and the sourceless, ever-present mystery of rosewater. No, this was not New York. I was home.”

It was during this period back home, and during her long and happy marriage to Abol, that Monir flourished as an artist, beginning with her winning a gold medal for her display at the Iran Pavilion in the 1958 Venice Biennale.

Image copyright

Image copyright

The Third Line

Monir had seen mirror mosaics before that day in the mausoleum in Shiraz – the style had been used elsewhere in Iran – but none had affected her in quite the same way. There was a practical reason for the style: centuries ago, mirrors that were imported from Europe had often broken by the time they had arrived, and so they were reused.

The style encouraged Monir to experiment: with shapes, with geometry, with building images up from their smallest fragments. Hexagons, the shape she later called “the softest form” that opened up more and more possibilities to link shapes, began to feature prominently in her work.

“I read up on Sufi cosmology and the arcane symbolism of shapes,” Monir wrote in A Mirror Garden, “how the universe is expressed through points and lines and angles, how form is born of numbers and the elements lock in the hexagon.”

Read about other notable lives

Monir’s research took her across Iran and her curiosity about her country grew.

She began learning from Iranian craftsmen trained in cutting mirrors like butter and in kneading plaster to make it pliable, and spent time with Turkmen silversmiths, studied an ancient observatory and worked alongside archaeologists. This week, one of Monir’s regular exhibitors, the Third Line gallery in Dubai, said she would always be known for her “eternally young and curious spirit”.

Over the years, Monir became an avid collector of fine silverwork and folk art from across Iran, buying 1,600 paintings on glass from artists across the Gulf.

But much of it would be lost years later, along with Monir’s own work and her Warhol print, as revolution swept Iran.

The Shah, Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, had led Iran through a programme of modernisation and Westernisation, but in doing so, he had alienated powerful religious and political forces.

After months of protests and strikes, the US-supported Shah and his family were forced to leave the country in January 1979. Two weeks later, Iran’s main spiritual leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, returned after 14 years in exile.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

Abol and Monir watched the Shah’s fall from New York, aware that Abol’s aristocratic background would make a return to Iran almost impossible.

Much of what they owned was now gone, they knew, as homes were seized by the authorities. “The best antiques and carpets found their way into the mullahs’ homes,” Monir wrote.

“Were my mirror mosaics hanging now on some mullah’s wall?” she wondered. “More than anything else, I regretted the loss of my drawings, not just because those sketchbooks had followed me all through my life, but damn it, they were really good.”

Most of the last 40 years of Monir’s life were spent in New York, and eventually saw her work exhibited to larger and larger audiences. The biggest challenge she had to overcome, she told the Guardian in 2011, was getting people to view Iran differently.

“In America, after the revolution, after the [Gulf] war, nobody wanted to do anything with Iran,” she said. “None of the galleries wanted to talk to me. And after September 11 – my God. No way. Rather than being a woman, it was difficult just being Iranian.”

Image copyright

Image copyright

Rose Issa Projects

Monir Farmanfarmaian in her workshop in Tehran

After Monir’s death, Middle East cultural historian Shiva Balaghi wrote that Monir and Abol would often walk by the Guggenheim Museum in New York as it was being built in the late 1950s. One day, Monir told Abol, she would exhibit her art there.

That day came in 2015, with one of her largest shows yet, Infinite Possibility. Abol, with whom she had another daughter, was not there to witness the show, having died of leukaemia in 1991.

There was time for one last move back to Iran, where Monir continued working with the craftsmen she so valued.

She was critical of the direction the country was taking, telling the Guardian in 2011 it was becoming “more devilish and more awful” with “these stupid Islamist things”. One work, Lightning for Neda, was produced in tribute to a young Iranian woman, Neda Agha-Soltan, shot dead during protests in 2009.

But her work had a receptive audience in Iran, and in 2017 the Monir Museum – the first Iranian museum dedicated to the works of a female artist – opened in Tehran. It was here that a memorial to Monir was held by her friends on Thursday.

“All my inspiration has come from Iran – it has always been my first love,” she said when the museum opened.

“When I travelled the deserts and the mountains, throughout my younger years, all that I saw and felt is now reflected in my art.”

Image copyright

Image copyright

The Third Line

All pictures copyright